With the upcoming Tremor release, 0.9.0, we're moving from threads as a basis for ramps and pipelines to async tasks.

Let's talk about why this is significant, what is changing, and how the architecture is changing.

Note that this is not a comprehensive treatise on threads or async tasks.

The Tremor That Was (threads)

Threads are a basic building block of programs that run multiple pieces of code concurrently. The operating system is responsible for coordinating across competing resource demands.

The OS can preempt, pause, and resume threads. We can leverage infinite or tight loops without the risk of completely blocking the system. These guarantees make concurrent code more accessible, with tools likecrossbeam-channels to build upon.

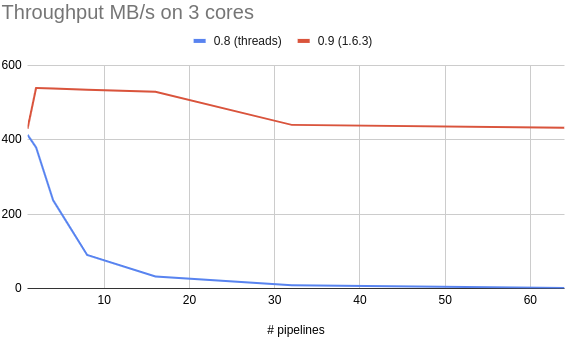

Threads work especially well in use cases where the system and logical concurrency models are well aligned; or, we can map application threads to logical cores on the system being used. Each thread can happily work away on its part of the logic and pass the result on to the next. The one thread per core model is what tremor 0.8 and earlier used. We had a thread for the onramp, a thread for the pipeline, and a thread for the offramp. As the computational cost of decoding, processing, and encoding was often in the same ballpark, this worked exceptionally well. We managed to push up to 400MB/s of JSON through the system this way (including parsing, tremor-script logic, and serialization).

This design can degenerate badly if there are more ramps and pipelines than cores on the system in use. Throughput degrades rapidly (as in up to 2 orders of magnitude worse at 30:1 ratio). At the time of writing this, the deployment model was one pipeline/ramp group on a four-core system, so it worked well in practice.

However, this places a burden on operators having to think about concurrency and parallelism to tune tremor for optimal performance and capacity.

In SMP systems, we observe other undesireable effects: The moment two communicating threads don't share the same underlying cache, performance plummets. This scenario exists when threads reside on two different CPUs or CCXs (thank you AMD for making me learn so much about CPU caches). As long as two communicating threads share the same cache, data shared between them can avoid trips to main memory and cache coherency protocol overheads. When two threads communicate across different caches, reads/writes may catastrophically collide and introduce overheads that drastically reduce overall performance.

Async/Futures

Futures, and in rust async/await (short async from here on), work differently than threads. With threads, the operating system has ultimate control over which thread is scheduled to work when. With async we can more flexibly manage scheduling in application code. This has many advantages in systems software.

Instead of the operating system preempting a thread, tasks require coordination within the application. The advantage is that since we can control where we take a pause, we can provide soft guarantees that the thread of control yields to the task schedulers in a way that better fits the application. A good example is async-io, where we allow another task to work whenever we have to wait for some IO.

In Tremor, we use channels extensively to coordinate event flows. They connect sources, sinks, and pipelines. Every time a channel is empty or full, we have to wait for a event that fills or drains a now blocked channel: This is a good juncture to let other tasks get ahead with their work. In tremor, these opportunities are fairly common.

The cooperative model is not without issues: If we select the wrong time to let other tasks work, we can hurt performance or even break the system. Giving up control in the right moment is especially tricky since it is sometimes happening implicitly. A task that loops without yielding forever is an extreme example. In OS managed threads, the OS can preempt a thread of control, so this is a non-issue. In user-managed tasks, however, this is an issue that needs to be protected against.

In rust, calling .await is effectively, not a guarantee. We cannot know if an async function ever yields. We can ensure that we yield control via yield_now. However, this comes at a cost: namely, that we might yield in situations where it is not strictly necessary.

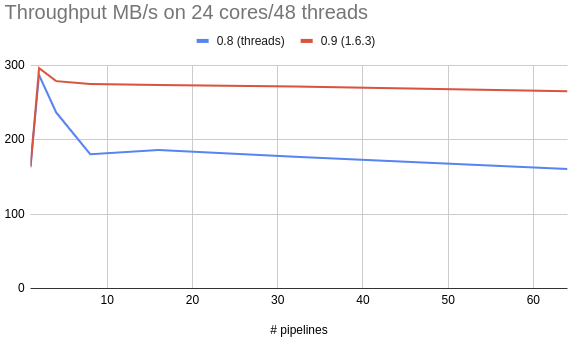

With regards to performance, tasks are typically cheaper from a context switching perspective, and we have finer grained control. On the other hand, we lose control over where a task runs, while we can pin threads to cores to schedule affinity on SMP systems, tasks may migrate across cores or runners move freely.

In Tremor, we have adopted the smol small and fast async runtime. When two tasks can run consecutively on the same executor, smol will schedule them in different executors. A significant improvement over the thread-based tremor runtime is that smol does not aggressively steal work from other schedulers if they are not overloaded. This avoids the runtime trashing CPU caches based on micro-benchmarking results.

Behavioural Improvements

In previous releases of Tremor, the runtime focused on situations where applications had a limited and bounded number of stable long-lived concurrent pipelines in each instance. While multiple running artefacts were supported, in practice, tremor was deployed on systems with up to 4 logical cores.

This works exceptionally well with plain old threads. Starting with v0.9, Tremor is expanding to support an arbitrary number of running artefacts in a typical running instance, with a different logical core topology than production deployments to date.

Deploying a higher number of pipelines per instance changes our needs of the underlying concurrency mechanisms considerably. The plain old threads design will no longer scale to meet these changing requirements and the move to task-based scheduling with executors favours emerging workloads whilst incurring a negligible overhead to classic tremor workloads.

Initial Results

Ab initio, the switch has some practical implications, mainly an improvement in performance.

In Tremor v0.8.0, colocating pipelines required careful capacity planning and tuning by experienced operators. In tremor v0.9.0, this constraint has been lifted and the capacity planning burden drastically simplified. Improvements in smol itself over the last few versions means that we have broken the 500MB/s throughput barrier for the first time with the new task-based runtime, which is quite a nice bonus.

Let's end with some pretty graphs. After all, a picture says more than a thousand words.

As a short explanation, this uses the json-throughput benchmark we have developed for Tremor running with deployments of one onramp, one pipeline, and one offramp to 64 onramps, 64 pipelines, and one offramp.